WHAT IS ANEMIA?

Anemia refers to the reduction in the oxygen-carrying capacity of the red blood cells (RBCs) in our blood. This results in an increased feeling of tiredness, fatigue, low energy, and weakness, along with a paler appearance (pallor). Other symptoms can include dark circles under the eye, dizziness, headache, lightheadedness, palpitation, and shortness of breath.

DIAGNOSING THE TYPE AND CAUSE OF ANEMIA

The basic lab test for anemia is a complete blood count (CBC) where a reduction in hemoglobin (Hb) indicates both the presence and severity of anemia. Hb of <11g/dL is usually labeled as anemia, while a Hb of <7g/dL is regarded as severe anemia. Often the RBC count or the hematocrit (% of blood made up of RBCs by volume) may also be decreased.

Some other parameters in the CBC help to diagnose the type of anemia and thereby find possible causes. Out of these the MCV (mean corpuscular volume) and MCHC (mean corpuscular Hb concentration) are useful indicators.

Normocytic Normochromic Anemia

The CBC shows decreased Hb with normal MCV and MCHC.

This is usually caused by blood loss, increased destruction of RBCs (hemolytic anemia), or suppression of the bone marrow (aplastic anemia).

Blood loss may be sudden, as seen in acute hemorrhages (traumatic, or spontaneous like in the case of using blood thinner and anti-clotting medicines, or if blood vessel abnormalities are present). Chronic ongoing blood loss is seen in infections (like TB, and parasitic infections: malaria, or hookworm infestations); bleeding from gut ulcers, polyps, or piles; inflammatory bowel disease (IBD); some cancers (like mouth, stomach, and colon); and menstrual factors in women (heavy bleeding or bleeding in between periods).

Hemolytic anemia can be immune-mediated (auto-immune), due to inherited diseases of RBCs (like sickle cell anemia, and spherocytosis), or exposure to toxic chemicals or poisonous substances.

Bone marrow suppression (aplastic anemia) can occur due to an immune-mediated cause or use of chemotherapeutic drugs, radiation, certain viral infections, a decrease in thyroid function, or exposure to toxic chemicals. The CBC may show a drop in counts of RBCs, as well as WBCs (white blood cells) and platelets. The reticulocyte count (proportion of new young RBCs) test can help give a clue, as it is low in bone marrow suppression and high in other causes of anemia. A bone marrow biopsy can give a definitive diagnosis.

Chronic kidney disease can lead to a decrease only in RBCs as a result of the reduced levels of the kidney hormone erythropoietin, which stimulates the production of RBCs.

Microcytic, Hypochromic Anemia

The CBC shows decreased Hb with decreased MCV and MCHC.

This is typically seen in iron deficiency and is one of the most common causes of anemia in many developing countries. Iron helps to make up the ‘heme’ component of hemoglobin which carries oxygen. Apart from insufficient dietary intake of iron, gastrointestinal diseases may also impair the absorption of dietary iron. Many of the conditions mentioned above which cause chronic blood loss, can also lead to iron deficiency. Therefore, the blood picture of anemia due to chronic blood loss or iron deficiency can be initially normochromic normocytic and then become microcytic hypochromic. Iron deficiency is more common in women due to monthly blood loss in periods, and also due to increased demand during pregnancy.

Further to CBC, iron studies or iron indices help in establishing the diagnosis which shows a decrease in total blood iron, an increase in total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), a decrease in the saturation of transferrin (the protein carrying iron in the blood), and a decrease in ferritin (the storage form of Iron).

Inherited defects in hemoglobin (like thalassemia) are also causes of microcytic hypochromic anemia.

Macrocytic Anemia

The CBC shows decreased Hb with increased MCV.

This is seen with a deficiency of the vitamin folic acid (B9) and B12 and can occur due to gastrointestinal diseases like malabsorption disorders, sprue, coeliac disease, IBD, and surgical removal of part of the gut, all of which may impair the absorption of these vitamins. Folic acid and B12 are required for the maturity of RBCs, and their inadequacy increases the number of immature larger RBCs (large ‘blast’ cells). This picture may sometimes also be seen in bone marrow suppression where there are more immature big blast cells. Therefore, this type of anemia is also called megaloblastic anemia.

Vitamin B12 requires a protein secreted by the stomach called the intrinsic factor (IF) with which it forms a complex that is then absorbed by the small intestine. Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune condition, where the body’s immune system attacks and destroys the IF, thereby preventing Vitamin B12 absorption.

Sometimes large RBCs (due to fat deposits) may be seen in anemia in people with liver disease or alcohol abuse. This is non-megaloblastic macrocytic anemia.

MCHC may be normal or even low in macrocytic anemia.

Dimorphic or Mixed Anemia

It is not uncommon for people to have multiple vitamin-mineral deficiencies like that of iron, folic acid, and B12. In such cases, the CBC may present a macrocytic picture due to a lack of folic acid and B12, and mask the iron deficiency. Even a bone marrow test may show blast cells and therefore confirm a macrocytic type of anemia. Therefore, blood tests ordered for anemia should include iron studies, folic acid, and B12 levels in addition to CBC to get a complete diagnosis.

ANEMIA – HEALTH MEASURES

Anemia not only causes a suboptimal functioning of many organs due to decreased oxygen delivery but also increases the load on the heart, thereby being a significant comorbidity with heart failure, especially in people with pre-existing heart disease. Anemia in pregnancy can also impact both the mother and fetus adversely and increase the complication rate. Therefore, prompt and meticulous management of anemia is of great importance.

Once the diagnosis, type, and severity of anemia are established, it is important to investigate for any underlying disease causing the anemia. Additional blood tests like liver, kidney, and thyroid function tests, bone marrow biopsy, stool test, endoscopy or colonoscopy, and hormonal evaluation in case of menstrual irregularities may be recommended in required cases. Vitamin D level should also be tested as its deficiency is sometimes associated with anemia or its symptoms. The management involves tackling the vitamin-mineral deficiency through diet and supplements and treating the underlying disease causing the anemia.

Diet

Important dietary sources of iron have been listed below.

- Eggs, Chicken, Meat, Fish, Clams, and Oysters

- Spinach, Broccoli, Peas, green beans and tomatoes

- Fortified Cereals like Oats and Wheat bran

- Chickpeas, Kidney beans, Soyabean, Lentils

- Almonds, Cashews, Walnuts, Figs, Prunes, Dates and Apricots

- Pomegranates, Apples, Bananas, Strawberries, and Watermelons

Animal sources of Iron (heme iron) are absorbed more readily by the gut and are thereby more effective than plant sources (non-heme iron). Women need more than twice the amount of Iron as compared to men, with their requirement further increasing 1.5 times more during pregnancy. Vitamin C, found readily in vegetables and fruits (especially citrus) increases the absorption of iron, while zinc (found in whole grains, legumes, dairy, nuts, and eggs) helps in the metabolism of iron.

Vitamin B12 is naturally found in animal products, including fish, meat, poultry, and eggs. Vegetarians can derive B12 from fortified cereals and milk products. Folic acid is readily found in plant sources like most green vegetables and fruits.

Supplements

Vitamin-mineral supplements are usually and commonly given orally. There is a wide variation in the amounts of iron, folic acid, and B12 in various supplements (single and combinations) available in the market. Supplements may also contain additional ingredients like zinc, vitamin C, and other B-group vitamins. The physician will select the appropriate supplement ingredients, dosage, and combination, based on the type and severity of deficiency detected.

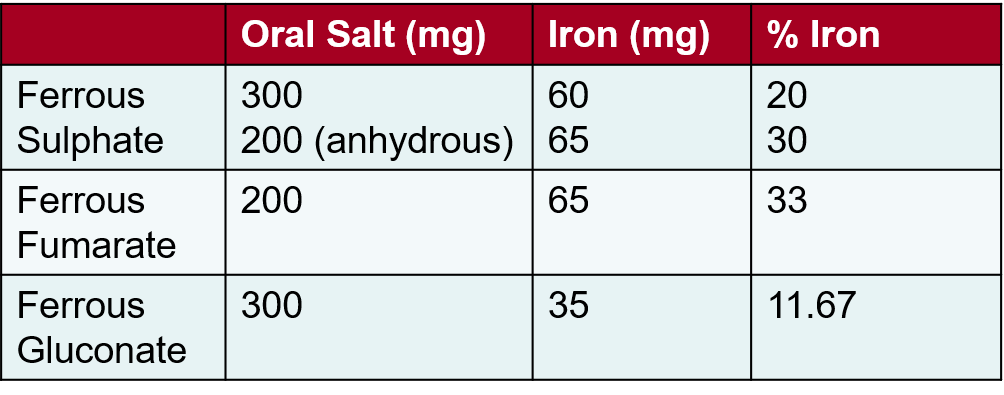

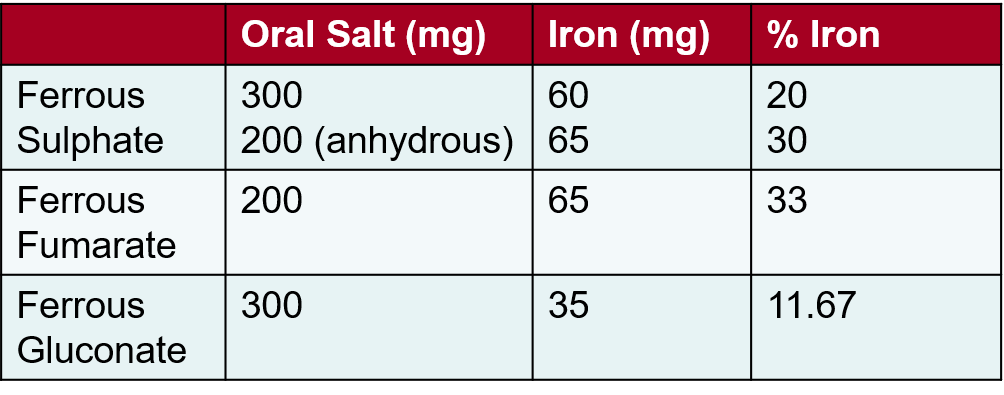

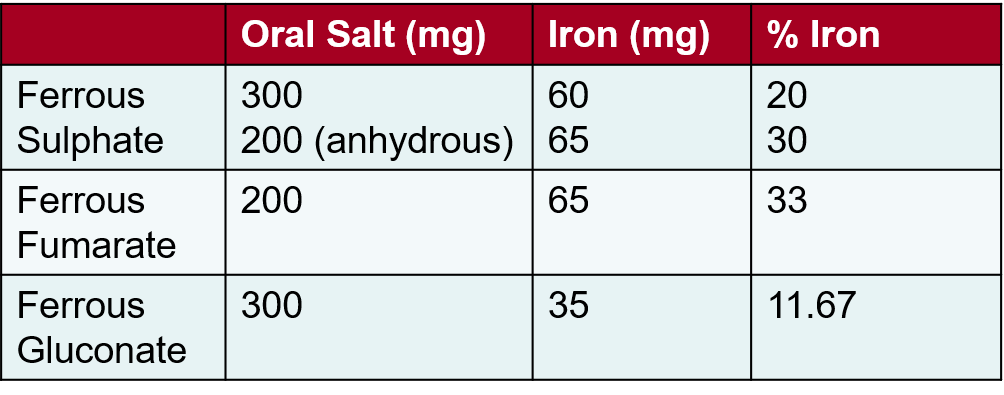

The common oral non-heme iron supplements are ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate, and ferrous gluconate.

Others include ferrous ascorbate (preparations usually contain 100mg elemental iron), iron-amino-acid complexes, ferrous bisglycinate, and carbonyl iron. Now liposomal micronized micro-encapsulated iron supplements are available that have the advantage of better absorption, more available iron at the site of action, and reduced gastrointestinal side effects. Heme iron supplements are also prescribed to improve absorption and tolerance.

It is important to dose iron supplements according to the amount of elemental iron in the supplement as the same amounts of different iron salts have different amounts of elemental iron. Most iron salts (non-heme iron supplements) show an oral absorption of around 10-15%., Absorption may be higher with heme iron supplements (20-30%) and liposomal iron (45-50%). Around 250mg of absorbed iron raises the Hb by approximately 1g/dL.

Oral iron supplements are best taken empty stomach or with a citrus fruit/juice. Avoid taking iron supplements at the same time as calcium supplements or antacids and keep at least an hour’s gap. Iron supplements are associated with gut disturbances like nausea, indigestion, and constipation. This could be reduced if the iron supplement is taken with meals, however, this decreases the gut absorption of iron by 1/3rd. Sometimes changing the iron salt, dosing on alternate days, or using heme iron or liposomal iron supplements may help reduce the digestive side effects and increase absorption.

Treatment with oral supplements should be continued for 3-6 months especially in case of oral iron to build up stores. Folic acid and B12 oral supplements are commonly available and well tolerated. Large oral doses of B12 (around 1000ug) is needed in pernicious anemia.

Supplements may be given as injections in the following situations: if there is a significant gut disturbance or intolerance when taken orally; absorption through the gut is expected to be poor as seen in certain gastrointestinal diseases like IBD, malabsorption and post gastroduodenal bypass surgery; if the deficiency is severe and stores need to be built fast (2nd/3rd trimester of pregnancy); and in chronic kidney disease. Injections may be given in single or multiple sittings at defined intervals, as an intravenous infusion. Common injectable iron preparations are iron dextran, iron sucrose, ferric carboxymaltose, iron isomaltoside, ferric gluconate, and ferumoxytol. For B12 and folate intramuscular/subcutaneous route of injection is available. B12 injections are given for pernicious anemia.

If vitamin D deficiency is also present, it may be treated with daily oral supplements, weekly shots/sachets, or a single injection, depending on the severity of the deficiency.

It is important to monitor response to treatment with periodic blood tests (2 weekly or monthly) to check Hb and the other parameters of CBC along with reticulocyte count, iron indices, folic acid, or B12 levels.

Further Reading-

For any query, additional information or to discuss any case, write to info@drvarsha.com and be assured of a response soon.

References